Cookbook development on the VMware platform

As cookbook development becomes a staple in the enterprise space, a repeatable process and standard steps need to be created. I have spent some time working with Chef customers and found a typical VMware based pipeline you should start molding to your environment. This isn’t a one size fits all, but it’s enough to get your use case off the ground.

One of Chef’s largest advantages is that we encourage you to shift changes and test earlier left, helping deal with infrastructure changes in development compared to finding issues in production.

Note: Thank you from here for the chart.

As you can see from the above chart, the cost of changes and work to your software is significantly higher in production compared to iterating on in development. This is important to call out, there’s no reason why we couldn’t use the same paradigm in cookbook development.

vmware-pipeline-example

I have developed an example cookbook with a pre-built pipeline to walk you through everything needed to start doing this type of development in a pure VMware SDDC. You can click here to see the code; and if your curious on the full pipeline leveraging Jenkins is here.

Eventually, you will want to take something like this example and create a cookbook-generator from it so you don’t have to remember any of these settings and standardize on it.

There is a Jenkinsfile, that with a few changes to this it the jenkins pipeline can be dropped in and “just work” (TM). An experienced Jenkins user or maintainer should be able to understand it pretty quickly.

The pipeline explanation

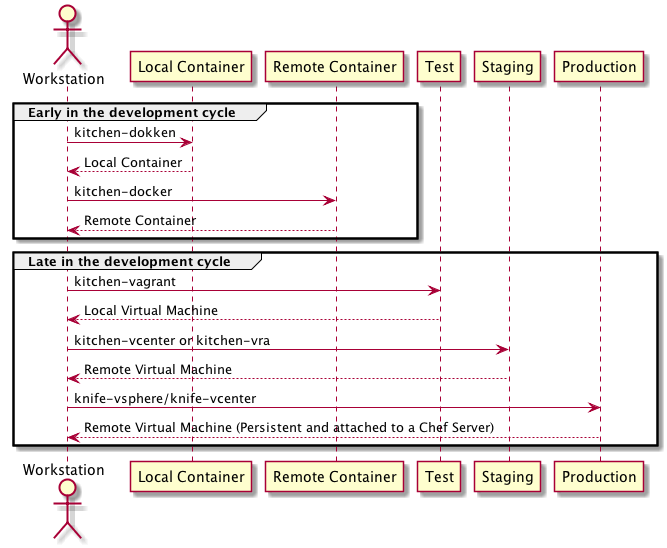

This whole explanation assumes you want to make a change to a cookbook that will change something that will change in production. We are going to focus on two halves of the development cycle, early and late to describe this iterative development process.

Early in the development cycle, you want to focus on quick changes, a fast feedback loop of what will affect your eventual outcome. Leveraging containers at this stage is not a perfect match, but pretty damn close and we even have two ways you can leverage it.

kitchen-dokken is a tool that allows for test-kitchen to talk to a docker endpoint and spins up 3 containers

for a converge. This is very specific to the Chef ecosystem but allows for unbelievably fast iterations on changes.

The three containers are a cookbook cache (where the cookbook code lives), a chef container (where chef is installed to), and

an OS mounted container where the two other containers can talk to. This creates a 3 tier system where one change

doesn’t need to blow away the complete stack, only changes out the container it needs to. Every change you make only

recycles the OS container and bind mounts the other two so you only change the code and not have to bootstrap chef or

kitchen every iteration.

kitchen-docker on the other hand is a pure docker driver for test-kitchen and in essence

creates as close as you can to a full operating system. Instead of the kitchen-dokken flow of creating

three containers, it only bootstraps one and emulates a virtual machine.

In the example code, you’ll notice that you can use kitchen-docker on remote hosts. I should say this is also true

with kitchen-dokken but for this example dokken is local, and docker is remote. If you work at a company that

doesn’t allow VirtualBox or VMware Workstation

using a remote docker endpoint might be the answer. This gives you a secure place in your VMware SDDC to have

a docker endpoint allowing for this quick iterations for early is your development cycle.

There is a “drop in OVA” for a docker endpoint provided for you by VMware called PhotonOS. If your policies only allow you to run machines in SDDCs approved by your company, installing Photon OS directly from VMware can be the answer to getting this endpoint. There is some work you need to do with the template, I cover the steps here.

After you’ve made your changes, updated your InSpec integration tests (for example) this is where you want to start looking at leveraging actual Virtualized Operating Systems. We do the best we can with containers but don’t forget this emulates as close as we can to full Operating Systems, but we do fall short. It’s important to say after you get the container to the place you want it with your recipe, writing the InSpec integration test as a “safety blanket” can help your future self.

At this stage is where kitchen-vagrant or if you can’t use vagrant, going directly to kitchen-vcenter or kitchen-vra and the longer iterations will start

happening. Depending on the machines vagrant, vCenter, and vRealize Automation have wildly different

spin up cycles, ranging from single minutes to tens of minutes. But the major advantage here is you can run exactly what

you run in production here, from the versions or templates in vCenter, to the specific Catalogs for vRA.

It should be clear here that these machines are ephemeral, and test-kitchen is not a deployment system. It’s a testing

framework that allows you to quickly iterate with only a few commands. You want to get to the point where a kitchen test

passes without any errors and all your check marks are green, before uploading this cookbook to your Chef Server.

When you are ready to push this change to production, this is where leveraging knife and the knife plugins

come into play. Upload the cookbook to a new version, and let chef-client run, or if you haven’t created the

machine yet, use something like knife-vcenter or knife-vrealize to create a persistent machine with the new code

bootstrapped with Chef.

From here you have the full cycle. With this example cookbook, it demonstrates everything up to the point of pushing it to a Chef server and bootstrapping a machine. This is by design, there are too many options to cover here, and hopefully, this triggers a way to get this pipeline working in your environment.